by Angela Braun | Apr 18, 2024 | Bodycare

Before you start making your very first batch of soap, you should be familiar with the process. Please read this soapmaking step-by-step instruction thoroughly to make sure that your first soap – and the many soaps to follow – will be a smashing success!

It’s most likely that you’ll make your soap in the kitchen. Before you start, remove everything from the surface that’s got nothing to do with soapmaking and protect the surface with a plastic layer (a dustbin liner that’s been cut open or a plastic tablecloth cloth for example). Lye splashes may damage your work surface in the long run. Keep some vinegar at hand as it neutralizes soap batter or lye splashes. Make sure that you have enough time and solitude for soapmaking, no pets or children should be allowed. The most important thing, however, is to observe the safety guidelines.

Step 1: Lye preparation

Weigh the water (or cool tea or coffee) into a heat-proof container (plastic or glass). Keep your rubber spatula close at hand.

Get on your household gloves, safety goggles, breathing mask and apron. Wear all that safety gear until the soap batter is in the mould and all tools have been cleaned. Make sure that the room you’re working in is well-ventilated.

Weigh the sodium hydroxide into a plastic container, carefully so that there is as little dust as possible. Do not inhale the fine dust. If you’ve spilt some NaOH onto the surface, remove it immediately. Close the NaOH container as sodium hydroxide is hygroscopic which means it attracts water.

Now, slowly but steadily pour the sodium hydroxide into the measured water (never the reverse!) and dissolve under constant, gentle stirring. During this process, the liquid will generate heat, up to 80 – 100 °C and it’ll turn opaque. Toxic vapours will form now that must not be inhaled under any circumstances!

After 2 – 3 minutes the liquid becomes clear again and there should be no undissolved crystals on the bottom of the container. Let the lye cool down to the required temperature. To speed up this process, you can put the container into a cold water bath.

Step 2: Fats/Oils preparation

While the lye cools down, weigh the solid fats you want to use for your recipe and melt them at a low temperature. Take the pot off the heat and mix in the weighed liquid oils.

Check the temperature of the lye water and the oils. Both temperatures should be below 60°C unless it’s noted otherwise. Every soapmaker has their own temperature range they feel most comfortable with and works for most recipes. I prefer to work with temperatures between 43 and 45 °C, but that’s my personal preference and others may have different opinions.

Step 3: Additives

If you want to add fragrances, colourants and fillers, weigh them while the lye water and oils cool down. Your additives should be ready for use as soon as the soap batter builds a trace.

Step 4: Mixing the soap

When the fat/oils and the lye-water have reached the temperature you want to work with, pour the lye carefully (avoid splashes) into the oil mixture (never the reverse!) and mix with a whisk. Keep stirring until both liquids have combined well. Now, use your stick blender and immerse it fully into the batter. Never turn on the stick blender until it’s fully submerged! As most blender motors aren’t strong enough to mix for an elevated time, put the blender off from time to time and stir by hand. The soap batter becomes slightly lighter and changes its consistency. It’s right when there forms a trace at the surface. When you pull out the blender and the mass that’s dropping down is clearly visible on the surface, it’s time to add the essential oils colourants and fillers. Work fast as the soap batter will thicken quickly after it has built a trace.

Step 5: Pouring the soap

Pour the soap batter into the mould and cover it with a cling film or a greaseproof paper to avoid the building of soda ash. As an alternative, you can spray the surface with 99% rubbing alcohol which also creates a barrier between the soap surface and the air. Soda ash is just sodium carbonate that forms as a white layer on the soap surface. It’s totally harmless and just a matter of aesthetics. You can even brush it off the surface so spraying with alcohol or covering is purely optional.

Step 6: Cover the mould

If you have covered the soap batter with cling film or greaseproof paper, you can put a towel over it, as well as around the mould, to insulate the soap. If you don’t use any physical cover, you can place a folded piece of cardboard or a similar item over the top of the mould so that it isn’t touching the soap and put a towel as insulation on it.

This technique helps the soap to initiate a gel phase which is encouraged for soaps with non-sugary liquids as a basis for the lye. Soaps that have undergone a gel phase harden more quickly and have bolder colours. If instead of water, tea or hydrolate you have used milk for example or fruit purees, the sugar that it’s in those additives reacts with the lye and naturally heats the batter. These soaps are not insulated to avoid overheating.

Step 7: Cleaning your work material

Before you clean your work material, rub off the soap batter thoroughly with paper towels to avoid too strong a contamination of your kitchen sink. Discard the paper towels in the dustbin. Remember that for cleaning, as well, you must wear your gloves as the soap batter can be skin irritating.

Step 8: Unmold and cut

Leave the soap in the mould for at least 2 days before you attempt to unmould it. Depending on the oils you used, it may take up to five days even, until the soap is hard enough to be unmoulded. The softer the oils (like olive or almond oil), the longer it takes the soap to harden. As a rule of thumb, if there is no visible mark when you press onto the soap surface, the soap is ready to unmould.

To unmould, pull the edges of the mould gently away from the soap, then lay it face down onto your work surface and slowly and gently press it out while gently rolling up the mould edges. If the soap doesn’t release smoothly or starts to crack or tear, leave it in the mould for another 48 hours and have another go.

Once the soap is out of the mould, you can cut it into bars. The bar size depends on the container you used and should be such that it comfortably fits into your hand. You can cut the soap with a sharp knife, serrated or non-serrated. Cut straight through the soap and slide the soap off the blade, otherwise it may break or tear.

Step 9: Curing

The soap bars must be cured in a well-ventilated area for four to six weeks before you can use them. I usually put the bars on greaseproof paper with a distance of about one centimetre. Turn the bars around several times during curing to make sure that they cure evenly. During that time, excess moisture evaporates, the soap becomes milder and the lather will improve. After curing time, you can measure the pH value with an indicator strip. It should be between 7.5 – 9.

Step 10: Storing

Store your cured soap bars in containers that are protected from light and at room temperature (or cooler). I usually use old shoe boxes. Light protection and a cool temperature are especially important for soaps with natural dyes and essential oils. Under the influence of light, the dyes will fade and heat makes the essential oils evaporate.

Now that you know the basic soapmaking technique, you may want to start with a beginner-friendly soap recipe like this one. Have fun!

by Angela Braun | Apr 18, 2024 | Bodycare

Soap is the oldest and most used washing detergent in the history of mankind. The oldest soap recipe that has been found is thousands of years old! And the best thing is: we still know how to make soap. The process differs a bit from that of our ancestors; after all, who would want to make lye from wood ash and boil it for hours with animal fats until it becomes a (stinky) bar of soap? The chemical principle or rather, the science behind soapmaking, however, stays the same and understanding the science behind it helps you to avoid mistakes, create your own recipes and stay safe during the process.

I was never good at chemistry, however. On the contrary, all things chemistry have always been a bit like magic for me. I mean, you take one thing and bring it together with another and you get something completely different! Weird, huh?

In this post, therefore, I will explain all this science stuff very simply – because that’s how I get it best. And I hope you, too.

The science behind soapmaking: What is soap?

Let’s start with the most mundane question: What is soap?

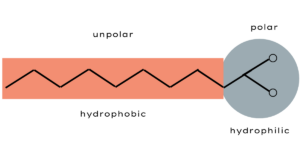

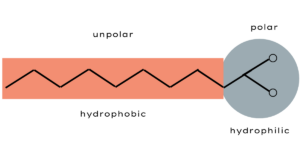

Soaps are surfactants and are used in combination with water as a cleaning agent. Surfactants are wash-active substances that reduce the surface tension of liquids. By that, they cause two normally immiscible substances, for example fat and water to unite. Why is that so? A fat molecule consists mostly of long chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms. The electricity is evenly distributed in these chains and therefore fat molecules are electrically non-polar.

Water, on the other side, consists of a negatively charged oxygen atom and two positively charged hydrogen atoms. Due to their structure, one side of the water molecule is negatively and the other is positively charged. This uneven distribution of charge is called “polar”. The negatively charged oxygen side attracts the positively charged hydrogen side of another water molecule like a magnet which is why water molecules are usually formed into clusters. They can’t, however, connect with the non-polar fat molecules.

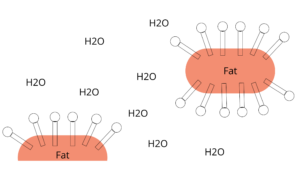

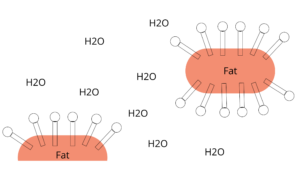

Soap, now, works as an “agent” between fat and water on their molecular basis. The soap molecules have a water-attracting (hydrophilic) and a water-repellent (hydrophobic) side.

The hydrophobic side attracts fat and encloses the fat droplets in small circles. The hydrophilic end connects to water. The result is an oil-in-water mixture, a so-called dispersion.

By washing (that is rubbing your hands), the fats contained in the dirt come off and the fat-dirt-dispersion is rinsed off with water.

I told you: it’s magic!

What is soapmaking?

I’d love to have a time machine and go back to that one day when someone discovered by accident that by cooking fats with alkaline pot ash you’d get a washing-active substance that dissolves dirt and fat.

The principle of breaking down fats with alkaline substances (that is: lyes) has not changed since that first day of soapmaking. Today, we know the chemical reaction of soapmaking, in chem-talk also known as saponification. As lyes, we use sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide. When saponification is carried out with sodium hydroxide we get hard soaps, with potassium hydroxide we get soft to semi-soft soaps. The lye breaks down the fat into soap (or water-soluble alkaline salts) and glycerin, or, in chem-talk:

Fat + Lye = alkaline salt (soap) + glycerin

Plainly said: Fats react with lye to create a soap with a small amount of glycerin through saponification.

In soapmaking for skin and hair, we use a sodium hydroxide solution as a lye. Sodium hydroxide can be bought as crystals or flakes and it needs to be dissolved in a liquid (mostly water) so that we can mix it with the oil.

Saponification value

When lye is added to a liquid, an exothermic (=heat-producing) reaction occurs. It’s fascinating to watch the red bar on the thermometer climbing up! When we use water, temperatures reach about 90 – 100 °C, when other liquids are used the temperature is often hotter.

The amount of lye needed to make soap depends on the oils used and is called the saponification (SAP) value. Oils are made of short- and long-chain fatty acids which dictate the amount of lye. For example, coconut oil contains about 85 percent saturated fatty acid which is responsible for the fact that palm oil is solid at room temperature. Olive oil, on the other hand, contains mostly unsaturated fatty acid which makes it liquid at room temperature. Coconut oil reacts radically differently than olive oil when mixed with sodium hydroxide and thus, both oils require different amounts of lye to turn them into soap.

Superfatting

As described above, soap works by clinging its lather to dirt, both of which are rinsed away by water. This process, however, can also take away the skin’s natural oils. To prevent the skin from drying out after washing, we add extra oil to the soap, a process called “superfatting” or “lye discounting”.

If we make soap with a recipe that uses the exact amount of lye that is necessary to turn all the oil into soap has a zero percent lye discount or is zero percent superfat. That means it has no excess oil after saponification which makes it a hard bar of soap but is not very gentle to the skin.

A soap with excess oil, on the other hand, makes a softer bar of soap that has a decreased shelf life.

Most soapmakers keep their superfat to under 10 percent, I mostly use superfats between three (hair soap) and nine percent.

Different methods of soapmaking

There are different methods of soapmaking.

Hot-Process

To accelerate the breaking down of the fats, we heat the soap batter to 100 °C, accelerating the reaction as well as water vaporization. When the soap has cooled down, the process of saponification is finished.

I haven’t tried out this process yet but it’s only a question of time.

Cold-Process

Here, no external heat is added but the chemical reaction releases heat (= exothermic reaction). Saponification takes a longer time (24 – 48 hours) and we have to leave the soap for that time in a mould. Afterwards, the soap must be cured for several weeks before it is ready to use.

This is the classic method for making body and face soaps and I have loved it since the first soap I made!

Melt and pour

With that method, you melt a premade soap base, customize it with fragrances and colourants and pour it into a mould.

This is a method I don’t use.

The science behind soapmaking: Ingredients

As described above, soap consists of fats and lye and – if you like – additives. Let’s have a closer look:

Fats

Our basic raw materials are oils or fats of plant or animal origin. The most commonly used fats/oils for soapmaking have a high content of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids like olive oil, coconut oil, palm fat, babassu oil and high-oleic oils like sunflower oil, rapeseed, peanut and safflower oil.

These fatty acids make solid soaps with a good storage time.

By a skilful combination of different fats and oils, the soaps’ characteristics can be optimized. That’s why we use mostly mixtures of fat/oils.

Lye

To produce solid hand and body soaps we saponify fats/oils a lye made of water and sodium hydroxide (NaOH). This lye has a pH value of 14 and therefore is strongly alkaline. NaOH is a white hygroscopic (i.e. water-attracting) solid and can be bought as crystals or flakes.

Any lye is a hazardous substance! You must know the risks and dangers and be very careful when working with it!

Additives

Depending on the purpose of our soap, we can add additives to optimize its properties or enhance its sensory effects. However, additives should be used sparsely and only in the best possible quality.

Fragrances

Although fragrances make only a small part of the overall soap amount, they determine (together with colourants) the first impression and influence our perception.

Essential oils

Essential oils are mostly gained by water vapour distillation of aromatic plants. Their shelf life varies with oils from citrus fruit having the shortest. We differentiate:

- untreated essential oils (gained from the plant)

- natural essential oils (consisting of several untreated components which haven’t all been gained from the plant it’s named after; no synthetic additives)

- nature identical essential oils (synthetic oils, composed acc. to a natural model)

- natural / nature-identical essential oils (mixtures of untreated and synthetic oils)

- artificial essential oils (artificial fragrances; often classified as health critical

Essential oils are irritating to skin and mucous membranes (work safety!) and may cause allergies.

Synthetic fragrances

Nowadays, synthetic fragrances are commonplace. Production is cheap, they have a long shelf-life and replace essential oils in many products. However, synthetic fragrances are chemicals and may contain components that are harmful to the organism. they may lead to contact allergies and allergies through inhalation. They degrade slowly and accumulate in the air.

Fragrancing of soaps

Fragrances, even in a low percentage, influence the physical properties of soaps, for example their solubility, emulsification, hardness and brittleness. It is therefore recommended, to use 2 – 3 percent (related to the whole fat amount) at the most. In soaps or sensitive skin or children, fragrances should not be used at all.

All fragrances used in soapmaking must be alkali-resistant, that is they must not be affected by the lye. Additionally, they must withstand the temperature at soapmaking. Fragrances based on alcohol are unsuitable as alcohol disrupts saponification.

Colour additives

Chemically speaking, we differentiate between inorganic and organic colour additives. Further differentiation is made according to the colourant’s capability to dissolve in the application medium (soap, water or oil).

Colour additives are classified as chemicals and may cause contact allergies. Some are even toxic or are classified as environmentally dangerous. When using colour additives, you must observe the safety instructions.

Colourants

Colourants are chemical compounds that dissolve in the application medium and dye other materials. There are natural and synthetic colourants. Natural colourants can be of animal or plant origin, with animal colourants deriving from bodily fluids like gall or blood and plant colourants deriving from woods, barks, roots, fruits, leaves and seeds. Their quality depends on climate, area, soil properties, etc.

Synthetic colorants on the other hand show a consistent quality as they are made under standardized production conditions. They are light- and heat-resistant and have an almost unlimited shelf-life.

Pigments

Pigments are colouring substances in the form of very fine particles that don’t dissolve in the application medium. The smaller the particles the more intense the colouring. Pigments can either be inorganic or organic, natural or synthetic.

- Anorganic natural pigments are obtained from soils and minerals.

- Inorganic synthetic pigments are produced with different chemical procedures and in high quantities, for example iron oxide pigments, metal effect pigments, white pigments (e.g. titanium oxide)

- Organic natural pigments are made of animal and plant parts

- Organic synthetic pigments are unsoluble

Water

For soapmaking, normal, still water is good. Tap water is ok as long as it doesn’t contain too much lime. Alternatively, you can use hydrolates, and alcoholic beverages like wine beer or milk (of animal or plant origin). With alcohol and milk, however, the soapmaking process is slightly different as these two heat too much and thus must be treated differently.

Resume

You see now, as simple as soapmaking may be at its core, it’s also very flexible and adaptable. By mixing different oils, using alternative liquid possibilities, and adding fragrances and colours you have almost infinite possibilities to create your own recipes.

I’m sure you can’t wait to learn how to make your first soap, right?! Get acquainted with the safety instructions, look how it works and then: make your first soap with this easy beginner-friendly recipe!

by Angela Braun | Mar 21, 2024 | Bodycare, Preserving

As you know – at least if you’ve read my About Me Page – I work at a school. There, we have a contract with a local grocery distributor who delivers organic fruit or vegetables once a week for the pupils in primary school. Depending on the produce and size, some moms come over and chop the fruit (or veggies) into smaller pieces so that nothing gets wasted.

Last week, we got oranges, and I rubbed my hands with glee. When the moms came to prepare the oranges, I asked them to put the peels aside for me and in the end I got 2 bags full. My office smelled like an orange farm!

I was astonished, though, that they had never heard of the different uses for orange peel and so I decided this topic was worth a blog post. Just let me say this before you dive in: it is important and cannot be stressed enough that you solely use ORGANIC orange peels. Traditionally cultivated oranges contain way too many toxins, especially on the peels and the disadvantages outweigh the benefits by far.

#1 Candied orange peel

For decades I loathed candied orange peel because I only knew the store-bought version. It didn’t look or taste anything like orange at all and even today I’m not sure if there is anything remotely orange in it (except, perhaps, some artificial orange colour). Whenever I made Christmas cookies, gingerbread or other traditional baked Christmas goods that required candied orange peel, I either left it out completely or mixed it with fresh orange juice to a paste so that I would get in some of the flavours. Yet, I was never satisfied until I tried some at a local market in Italy. It was heaven! Juicy and chewy and bursting with flavour. Back home, I researched recipes for making candied orange peel by myself and you’ll be happy to know that it isn’t difficult at all!

Cut the orange peels into strips of about 0.5 cm.

If you want to dry them afterwards and use them as snacks, leave them like that. If you want to use them in cakes or cookies, cut them up into tiny squares.

Now, put them into a pot and fill up with water so that the peels are covered. Bring to the boil and let it boil for about 10 minutes. Pour the peels into a sieve and let them drain. Repeat the whole process twice and rinse the peels. This pre-cooking removes the bitter taste from the peels.

Put 0.5 l water into the pot and add 1 kg sugar or multiply the amounts if you have lots of peel. Just stick to the ratio of one part water to two parts sugar. Bring this mixture to the boil while constantly stirring until the sugar is dissolved. When the syrup is boiling add the orange peels and let it simmer for about 30 minutes until the peels are well cooked. Now, you either take the peels out onto a wire rack and let them dry for 12 – 24 hours until they are almost dry and still a bit sticky. Then put some sugar into a bowl, add the peels in portions and mix it through until the peels are well-covered in sugar. In the fridge, they will last for up to one week.

The other option is to put the cooked orange peel cubes into a glass jar and add some of the orange syrup so that the peels are covered in it. Close the jars with lids and once cooled down put them into the fridge. They’ll last for up to one year.

#2: Orange syrup

Don’t throw away the syrup from the candied orange peels. It’ll make an amazing flavour addition to water, cocktails, soda and more. You can even add it to some apple vinegar, pour about 20 cl in a glass and fill it up with sparkling water. This makes a wonderfully refreshing, non-alcoholic drink for summer.

#3: Orange sugar

For this recipe, you must remove the white part of the peel. Cut the peel into pieces, mix it with sugar and put it into a blender. Mix until the sugar and peel are powdery. Distribute it on a baking tray and let it dry in the oven at low heat until it’s completely dry. Let it cool down and store it in a tight container. Basically, it’ll last forever but it’s best consumed within a year of making it. Later, the flavour will go down.

#3: Orange powder

The production of orange powder is similar to orange sugar. You remove the white part of the peel and let the peels dry in the oven at low heat. When they are completely dry (make the “snap test”) and cooled down, grind them in the blender until they’ve become a powder. Use orange powder wherever you need a bit of orange flavour, i.e. cakes, salad dressings or savoury dishes.

#4: Orange salt

Remove the white part of the orange peels and cut them into very small pieces. Put the salt, the orange peels, some thyme and rosemary in layers into a glass jar and close it with the lid. After two weeks, the salt has taken on the flavours. You can either let it be as it is (this will make for a beautiful gift) or put the mixture in a blender and mix it until it’s powdery.

#5: Infused orange oil

To make infused orange oil, remove the white part of the orange peels and put them into a glass bottle. Fill up with very good olive oil and let it set for two weeks. Afterwards, drain the oil and remove the peels. You now have some great orange-flavoured oil that you can use for salad dressings, pasta sauces or even on your pizza.

#6: Orange-flavoured honey

Again, remove the white part of the orange peels and put the peels into a glass jar. Fill it up with honey – either the real thing or one of your homemade herb kinds of honey – and let it sit for 5 – 7 days. Drain the honey and use it in your tea or instead of sugar in a German Hefezopf for example.

#7: Orange butter

After removing the white parts of the orange peels, cut them into tiny pieces. Soften the butter by mixing it and then add the tiny orange peels and some salt. Mix well and form a roll. Let it sit in the fridge until it’s firm. Enjoy this butter on some homemade bread or with grilled meat. You can also freeze the orange butter so that you’ll have it available when the BBQ season starts. In the fridge, the butter will last for about one week, and in the freezer for up to 6 months.

#8: Ice cubes

This is a simple one: remove the white part of the orange peels, cut them into small strips and put them into ice cube forms. Fill up the forms with water and put them into the freezer. I love these orange ice cubes for all kinds of drinks as they don’t water them down but give them a subtle orange flavour.

#9: Orange peel vinegar cleaner

I love cleaning with this orange peel vinegar cleaner. Not only does it remove stains well, but it also smells really good – not at all like vinegar. To make your own orange peel vinegar cleaner, put some orange peels into a large jar until it’s about three-quarters full. Fill it up with white vinegar or vinegar essence and let it sit for two weeks. Remove the peels and fill the cleaner into a spray bottle. You can use this cleaner for removing water stains in the bathroom or for cleaning your kitchen surfaces. In short: everywhere you would use vinegar to clean.

#10: Orange extract for cleaning

After having removed the white part of the orange peels, put the peels in a glass bottle until it’s about three-quarters full. Fill it up with clear alcohol like vodka or schnapps and let it sit for two weeks. After that time remove the peels and put the bottle without a lid onto a sunny windowsill. The alcohol will evaporate. Sniff the mixture from time to time: if you can’t smell the alcohol any longer it’s ready. I love using this orange extract in my mop water and in our homemade laundry detergent.

#11: Orange sugar scrub

This is a fast, cheap and easy way to make a healthy body scrub with totally natural ingredients that will do your body nothing but good! Remove the white part of the orange peels and cut the peels into tiny pieces. Mix them with one cup of coconut oil, ½ cup of sugar and 3-4 tablespoons of orange juice. Put it into a glass and store it in the fridge for up to one week.

#12: Orange peel soap

As in the orange sugar scrub, finely cut orange peel makes a good peeling in soap, too. You can use any simple soap recipe, add finely cut dried (!) orange peel and some essential orange oil and use it as a peeling soap that smells great! For a simple orange peel soap recipe look here.

I know there are some more uses for orange peels out there but I haven’t tried them yet. I will, however, and every time I find some new ways to use orange peels, I’ll update this post. Stay curious!